On starting this unit, the area I felt most apprehensive about engaging with was faith, religion and belief. This stems from challenging personal experiences around religion, specifically Christianity, in education settings. I grew up in a non-religious household, but with culturally Catholic heritage on my mum’s side, as she is Italian. My parents never baptised me, leaving it open for me to choose as I got older. At age seven, while attending an Anglican school, a teacher told our RE class that non-believers would go to hell. I asked if this applied to my parents, as they weren’t religious. She looked me straight in the eye and said, “I’m sorry, but yes,” before encouraging me to be baptised.

I pursued religion for about a year after that interaction, until I gave it up (this is a longer story that I can’t fit into this blog post). Still, I had frequent nightmares about the fate of my family. As an adult and educator, I now see this moment as an abuse of authority. Crenshaw’s theory of intersectionality helps me unpack why this was so damaging, because it intersected with my vulnerability, age, family background, and the power dynamics inherent in education.

Belief is deeply personal, shaped by our complex positioning in society. Simran Jeet Singh (2016), describes how trying to paint an entire community of people with a ‘single brush stroke’ is a fallacy, and this really aligns with my thoughts around specificity, and the unique nature of each persons beliefs and life experiences. Crenshaw’s work reminds us that identity isn’t linear or one-dimensional; faith doesn’t exist in a vacuum, and neither do its consequences. As a teacher, I am often aware of the potential power imbalances in the classroom. In many ways, before starting this unit, I thought that not engaging with with faith, religion and belief felt like a way to keep students safe. However, on further reading, I realise this is not always the case.

To treat faith as ‘non-relevant’ is in many ways disrespectful to students and staff for whom their faith is very important within their lives (Dinham, A. et al). Ahmed (2012) argues that institutions often perform diversity without challenging the deeper norms that produce exclusion. Whilst watching Appiah’s talk, Is religion good or bad? (2014), I was also struck by how dominant paradigms like Christianity have historically been used as reference points for understanding “other” religions, often in the context of colonialism. This mimics broader systems of oppression where dominant structures marginalise those who fall outside perceived ‘normative’ categories. I see acknowledgement of student’s faiths, religions and beliefs as intrinsically connected to decolonial practices.

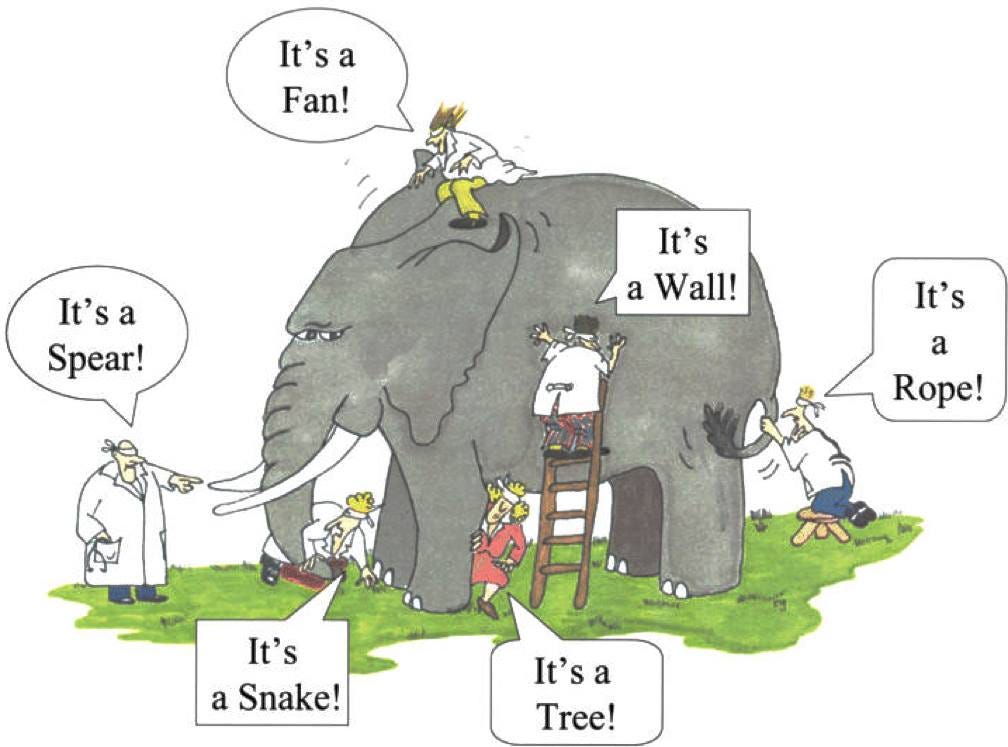

But then I wonder, how to hold all this complexity in an equitable way in the classroom? As the illustration below demonstrates, our beliefs are often shaped by our life experience, background and perspective, and finding ways to hear each other might help to find moments of understanding and connection.

I found Rekis’ article to be particularly interesting, as it demonstrates how religious identities are often filtered through assumptions tied to gender, race or visible markers such as dress and veiling. Within my artistic practice, I work on an intergenerational project with older women from East London and 14 year old students from Mulberry School fot Girls. Most pupils (98%) are practicing Muslims, most of whom (90%) are of British Bangladeshi heritage. The adult group are more diverse in terms of race, ethnicity and religion, and often in our preparatory sessions, we encourage the two groups to consider assumptions around the group they are about to meet. Many of the women are curious about the girls’ religious beliefs and their autonomy, particularly regarding wearing hijab. This aligns with what Haifaa Jawad writes around the polarisation of Muslims and the West, which are ‘are often based on lack of knowledge and understanding about each other’s lives’. I see reflected in so much of Reki’s writing how prejudgment can lead to mistrust and speech silencing, which is why in advance of the adults and children meeting, we meet the groups separately to discuss assumptions and stereotypes, creating space to reflect and challenge. This means that when the full group comes together, there is a deeper understanding of each other’s beliefs and perspectives. We then co-create a group agreement about how we want to feel in the room, to foster respect and dialogue. What emerges from this work is a beautiful holding of the intersections of the group, which doesn’t shy away from some of the frictions that could arise, and instead acknowledges them directly to build a space that is pluralistic and co-creative. In many ways, the visibility of the students’ religious beliefs makes it easier to tailor my approach to create equitable and just interactions, but I am conscious that within my classroom at CSM, faith and religion is often less visible and certainly less openly discussed.

Simran Jeet Singh’s reminder that “no community is a monolith” (2016) encapsulates the core of this blog. Each student’s identity is layered and unique. A personal goal is to review UAL data before term starts, so I can better understand the faith, religion and beliefs of each cohort as a starting point before getting to know them more personally. As Sara Ahmed argues, institutions may “perform” diversity while failing to change structures of exclusion. I must resist the false neutrality of secularism and instead acknowledge belief as an important facet of identity.

References:

Appiah, K. A. (2014) Is religion good or bad? (14 mins)

Ahmed, S. (2012). On being included: Racism and diversity in institutional life. London: Duke University Press.

Broughton, A. (2017) The Elephant-Sized Assumption, Medium. Available at: https://medium.com/@brought_on/the-elephant-sized-assumption-1f8c4d7153b5.

Dinham et al (2017) Threatening Bodies – Navigating Institutional Gendered Religious Racism.pdf

Trinity University (2016) Challenging Race, Religion, and Stereotypes in the Classroom. (3 mins)

Jawad, H. (2022) Islam, Women and Sport: The Case of Visible Muslim Women (6 mins)

Rekis (2023) Religious identity and epistemic injustice – an intersectional account File

Leave a Reply