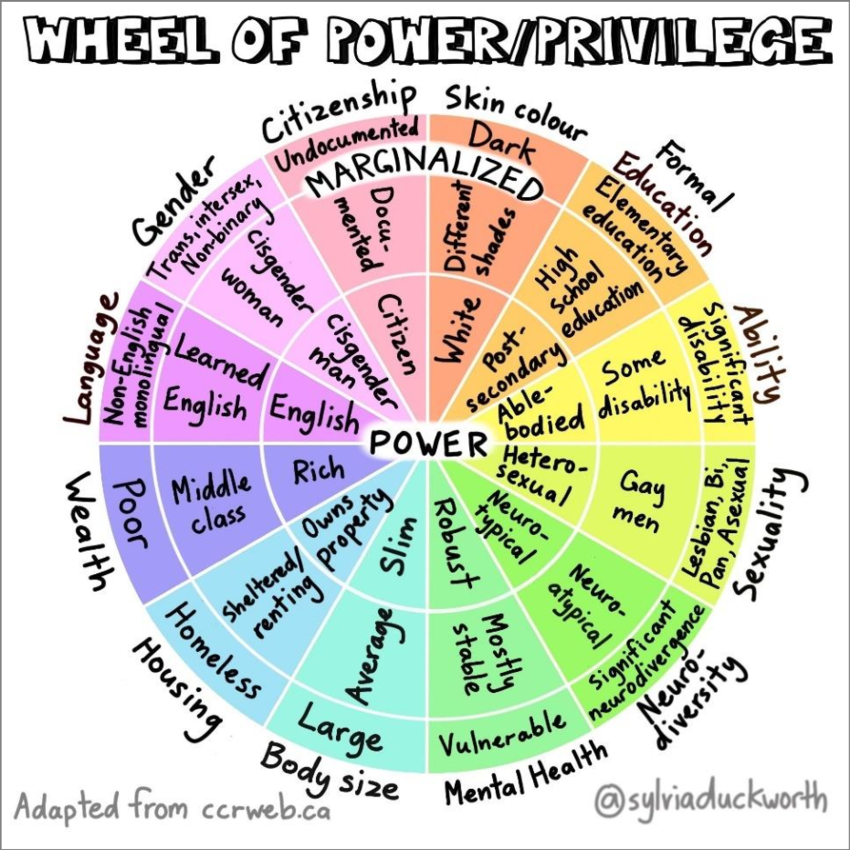

When considering inclusive practices around disability, I am inclined to approach it through the lens of the ‘social model of disability’ (Oliver, 1983), which argues that people are disabled not by their impairments, but by the societal barriers around them. These barriers are rooted in systems designed to benefit those in positions of power and privilege. This connects directly to Kimberlé Crenshaw’s concept of intersectionality, which highlights how groups’ and individuals’ identities result in unique combinations of discrimination and privilege. To explore this, I use Sylvia Duckworth’s ‘Wheel of Power and Privilege’ – a reflective tool to map how different attributes (such as race, gender, ability, class) intersect. It works well alongside frameworks like the Social GRACES to provide a fuller picture of identity and proximity to power.

Societies built only for those near the centre of this wheel ultimately exclude everyone else. As Ade Adepitan said; “I am disabled because society has not allowed me to shine, not because of my disability.” He highlights how structural systems like transport often enforce “segregation by design,” further marginalising disabled people. The comparison in this interview to Rosa Parks bus protest further reinforces the longstanding nature of these inequitable social constructs and their intersectional ramifications.

This brings to mind a trans student I worked with who requested gender-neutral toilets. I contacted estates at CSM on their behalf, and asked for clarity and support in providing this facility. The proposed solution was to use the disabled toilet, which required a staff card and also doubled as a baby changing space. This example highlights how multiple marginalised identities, (eg. disabled people, trans people, mothers and birthing parents and those who hold some or all of these identities), are forced into a single, inadequate space, that is accessible only through institutional privilege. If the buildings toilets were designed to be inclusive and accessible, the entire community would benefit. With the support of my line manager and with the students consent, I pushed for more inclusive signage. Although some changes were made, it is still not enough and it is a frustrating reminder of how slowly the institutional cogs turn when it comes to meaningful change and inclusive practices.

The irony of beginning this unit in an LCC classroom only accessible by stairs reinforces this point. Who is left out of conversations on inclusivity when the space itself is inaccessible? Using the social model, buildings would include ramps, lifts, and accessible toilets throughout, not as afterthoughts, but as essentials. While this may seem costly or complex, such change is necessary for meaningful equity.

Structural change is needed, but also individual actions. Christine Sun Kim, in her TED talk, references Sara Nović’s tweet: “I can 100 percent promise that you learning sign language is easier than a deaf person learning to hear.” This highlights how resistance to stepping out of comfort zones upholds exclusion. In my micro-teaching session, I asked students to use “sign names” as an introduction, inspired by my work with Deaf theatre practitioner Jenny Sealey. Someone in the group fed back that students might find this uncomfortable as it is unusual and takes more confidence than just saying your name, but I would argue that this discomfort is crucial for those in power to confront. A hearing person can opt out; a Deaf person cannot choose to hear. Opting out contributes to exclusion.

As an educator, I strive to use my own privileges to advocate for inclusivity, and where I have less power, to communicate with those who have more to make change. As a result of this unit, I’m now implementing live captions in class to further my practice. This benefits not only Deaf students, but also the intersections of those who speak English as a second language and those have different learning styles, for example. Creating truly inclusive learning spaces requires ongoing reflection and action, and these resources are a welcome part of that development.

References

‘Christine Sun Kim in “Friends & Strangers”’ (2023) Art in the Twenty-First Century, Season 11. 20th October. Available at: https://art21.org/watch/art-in-the-twenty-first-century/s11/christine-sun-kim-in-friends-strangers/

Crenshaw, K.W., 2013. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. In The public nature of private violence (pp. 93-118). Routledge.

Duckworth, S. (2021). Figure 1. Wheel of Power, Privilege, and Marginalization, by Sylvia… [online] ResearchGate. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Wheel-of-Power-Privilege-and-Marginalization-by-Sylvia-Duckworth-Used-by-permission_fig1_364109273.

Graeae. (n.d.). Graeae | world-class theatre & training from D/deaf & disabled artists. [online] Available at: https://graeae.org/.

Partridge, K. (2019). Funded by the Department for Education PSDP-Resources and Tools: Social GGRRAAACCEEESSS and the LUUUTT model. [online] p.2. Available at: https://practice-supervisors.rip.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Social-GGRRAAACCEEESSS-and-the-LUUUTT-model.pdf.

SCOPE (2024). Social Model of Disability | Disability Charity Scope UK. [online] Scope. Available at: https://www.scope.org.uk/social-model-of-disability.

www.youtube.com. (2021). Ade Adepitan gives amazing explanation of systemic racism. [online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KAsxndpgagU.

www.youtube.com. (2024). Intersectionality in Focus: Empowering Voices during UK Disability History Month 2023. [online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_yID8_s5tjc

Leave a Reply to Antonella Nonnis Cancel reply